As a key part of understanding what is to come, we are working through how to model the effects of modern-day mercantilism. In this report, we share some thoughts on that endeavor.

In 1965, Time magazine published an article titled by a quote attributed to Milton Friedman: “We Are All Keynesians Now.” Ideas around using fiscal deficits to manage business cycles—once outside the mainstream—had become the mainstream and would go on to be a key driver of market outcomes in the decades that followed. Those ideas then went dormant throughout the private-sector-dominated 1990s and early 2000s, before re-emerging after the global financial crisis.

In the period since the financial crisis, we’ve seen a similar creep toward modern-day mercantilism. With the election of Donald Trump, the transformation of US policy will take another dramatic step forward, and without the US’s protection, the previous global system of free trade and limited government intervention is hanging by a thread. For so many years, capitalists were concerned that socialism would end the Reagan/Thatcher economic system. Instead, modern mercantilism is poised to strike the final blow. We are all mercantilists now, and the implications are profound and unavoidable.

By “modern mercantilism,” we mean the following:

- The state has a large role in orchestrating the economy to increase national wealth and strength.

- Trade balances are an important determinant of national wealth and strength, and trade deficits are to be avoided.

- Industrial policy is used to promote self-reliance and defense.

- National corporate champions are protected.

Nearly everywhere we look, countries are heading in this direction:

- China has embraced many of these mercantilist policies for some time now, steadily scaling up support to its industrial sector in technologies like electric vehicles and batteries since 2010. President Xi has explicitly tied China’s development goals to the creation of an advanced manufacturing system, and since 2020 he has tied industrial policy planning to security goals and self-reliance.

- The US has shifted the most toward mercantilism over the past decade, with bipartisan support, though Trump’s return to the presidency will accelerate it. The broader catalysts have been 1) growing geopolitical tensions and the emergence of China as an economic power and strategic competitor, creating newfound worries about supply chain dependencies and the importance of a robust manufacturing and defense industrial base and 2) growing concern about the societal cost of lost manufacturing jobs, compared to the benefits of cheaper consumer goods and more market-efficient allocation of capital. Now the views of key Trump advisors like former US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer are becoming more widely shared: trade deficits are a transfer of wealth to other countries, tariffs are necessary to defend US workers from “beggar thy neighbor” industrial policies of countries like China, and a robust manufacturing base is critical for future productivity growth and national defense.

- In a world where some major economies shift to mercantilism, free-trade holdouts cannot survive. China’s and the US’s mercantilism are now pushing Europe down a more mercantilist path as well. While French President Macron has always been the tip of the spear in the push for a more independent Europe, his comments following the US election were a notable synthesis of the dilemma Europe faces: “The world is made up of herbivores and carnivores. If we decide to remain herbivores, then the carnivores will win and we will be a market for them.” More broadly, he lamented Europe’s tendency to “think we’ve got to delegate our geopolitics to the United States of America, that we’ve got to delegate our growth model to our Chinese customers, that we’ve got to delegate our technological innovation to the Americans.” There is not quite as broad a mercantilist consensus in Europe as in the US and China—the policies adopted thus far have been more measured, and there are still some efforts to uphold the WTO order. But the pressures to shift away from the free-trade order are building as the risks to Europe’s industrial sector grow.

We will continue working on understanding all of the implications, but the dynamics below are the ones that we believe are the most important at the moment and that we are working to build into our model of the world:

- Industrial and trade policy are becoming more impactful—now policy incentives need to be increasingly understood and reflected, in addition to market incentives. While there is a recognition of the role of entrepreneurship and market incentives in motivating technological innovation, policy makers are increasingly using tariffs, government subsidies and spending, export controls, and sanctions to steer parts of the economy toward outcomes that increase national power. Key objectives include eliminating supply chain dependencies, advancing domestic capabilities, and excluding competitors from keeping pace. National interests, rather than solely market interests, drive the creation and protection of large “national champion” companies that can contribute to a robust manufacturing base.

- A more mercantilist world creates significant challenges for growth in trade-surplus economies like China and Europe, which have been the most reliant on the existing global trade system. As the US—the largest trade-deficit economy by far—is likely to take steps to reduce trade deficits, surplus economies are likely to face headwinds. In the past year, China has been able to achieve its growth target through support to the manufacturing sector and export growth, while domestic demand has been weaker. Longer term, much of Europe’s—and Germany’s in particular—recovery from the financial crisis was driven by a surging current account surplus and a competitive, export-oriented manufacturing sector.

- The retaliation to mercantilist policies is likely to extend beyond tariffs. Countries that run trade deficits have the upper hand in trade conflicts limited to tariffs, because they have more imports to tariff than exports subject to tariffs. So competitor countries are likely to respond with a wider range of measures. A particular area of focus for us is the global profits of US companies, which has been a key driver of US equity exceptionalism and could be a target of countries seeking to respond to US tariffs.

The Policy Effort to Increase National Strength and Its Implications

The shift to modern mercantilism entails governments increasingly taking steps to actively manage the economy, in order to a) invest in capabilities that advance national power, b) eliminate supply chain dependencies, and c) limit competitors’ ability to compete. At the core of these is a focus on domestic manufacturing capabilities as a source of national strength.

The broader context for this shift is intensifying geopolitical competition and the weakening of the US-led order. Compared to the 1980s to early 2000s era, when countries were broadly liberalizing their economies and the US faced no major direct rival, China now increasingly challenges the US in a range of spheres—economically, militarily, and in areas like education and technology—and has “the intent to reshape the international order,” as stated in the White House’s 2022 National Security Strategy.

As a result, policy makers have become more focused on the explicit connections between the economy and projections of national power and are increasingly using industrial policy to develop industries that can contribute to geopolitical strength (like advanced technology sectors and a robust manufacturing base) and reduce reliance on foreign adversaries in critical supply chains and other imports. The table below highlights the state of industrial policy across China, the US, and Europe.

The charts below put recent industrial and trade policies in perspective. China is spending by far the most on industrial policy, followed by the US. Thus far, tariffs in the US have been relatively mild and mainly focused on China—though Trump’s latest proposals would be more sweeping if enacted, even in a pared-back form. The recent increase in industrial policy support under the Biden administration through measures like the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act have caused spending on manufacturing construction in the US to nearly double.

The main implications we see from this are:

- Government policy is growing as a relevant driver of profits and company performance. This mercantilist push is aligning company and government objectives, and we believe we will see growing examples of governments ensuring that companies critical to their manufacturing bases succeed even if they otherwise face competitiveness headwinds. This will entail some combination of directly supporting companies with industrial policy to give them a competitive edge and using tariffs to protect companies from foreign competition.

- A headwind to productivity growth and an upward pressure on costs. All else equal, these government policies will reduce the competitive pressures companies face, as their survival is a matter of national interest and not just the market’s process of creative destruction. Measures like tariffs, industrial policy, and export controls work to define a market for the kinds of companies the government wants to exist, rather than the market and what best serves it determining the success of companies. This isn’t to say that mercantilism will singlehandedly drive stagflation, as there remain a number of other supports to productivity growth (like AI), but it will be a countervailing pressure to those other secular dynamics.

- A likely cascading dynamic of growing tit-for-tat measures, in an environment of hampered global institutions. Because one country’s trade surplus is another’s deficit, industrial and trade policies in one country have the effect of setting industrial and trade policies in another if policy makers don’t respond with industrial and trade measures of their own. This means the mercantilist push for stronger industrial policy and more trade protectionism in some countries increases the chances of comparable measures in other countries—this is why Macron stated Europe can’t be an herbivore in a world full of carnivores. It has also undermined the norms and institutions that previously restrained the use of tariffs and other trade barriers, most notably the WTO. As president, both Trump and Biden have blocked new appointees to the WTO’s dispute resolution panel, meaning that the body has not been able to issue any rulings on members’ complaints that other members aren’t adhering to the rules.

Implications of the Push to Reduce Trade Deficits

A key dynamic of the post-Bretton Woods, highly globalized era is that the US has run relatively consistent trade deficits, absorbing the surpluses of most other economies. Since its entry into the WTO, China has been one of these surplus economies. The modern mercantilists see trade deficits as a key sign of national weakness. Persistent trade deficits imply the existence of import dependencies on other economies—sometimes geopolitical rivals—for critical goods. And modern mercantilists see the flip-side benefits of large trade deficits, like the US having the most robust capital markets in the world, as less clearly tied to national power and to benefits for workers when compared to the advantages of persistent trade surpluses, like large manufacturing bases.

As a result, the current system, where China comprises roughly 30% of global production but its share of global consumption is less than half that amount, is untenable. In fact, combatting Chinese industrial policy and the role it has played in driving large Chinese trade surpluses is an explicit focus of key Trump trade policy architects like Robert Lighthizer: “What we have seen in recent decades is countries adopting industrial policies that are designed not to raise their standard of living but to increase exports—in order both to accumulate assets abroad and to establish their advantage in leading edge industries...These are the beggar-thy-neighbor policies that were condemned early in the last century. Countries that run consistently large surpluses are the protectionists in the global economy…The US could use tariffs to offset the unfair industrial policies of the predators.”

The precise growth impacts will depend on the shape and scale of tariffs implemented. Here, we discuss how the broader shift toward mercantilism will create real challenges for key surplus economies’ growth models.

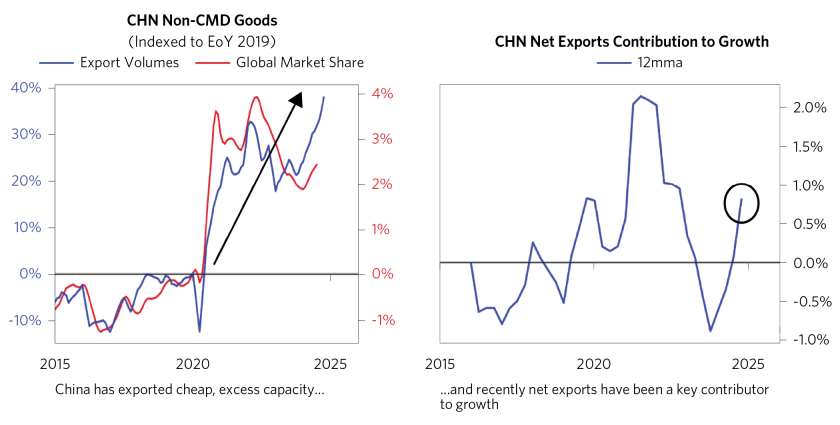

For China, exports and manufacturing-oriented stimulus have been a key driver of growth as household spending has remained depressed amid a broader deleveraging. As China has moved to transition away from a property-heavy growth model, it has steered more financial support toward its manufacturing sector. As a result, growth in industrial production has sizably outpaced growth in household demand in recent years, leading to falling prices and to China exporting its manufacturing surplus abroad. Over the past year, net exports have contributed about 1% to Chinese real growth—a key support as policy makers have otherwise faced challenges in hitting their 5% growth target. Rising tariffs—not just from the US but also from places like Europe—will turn net exports from a support to a drag, making it challenging for China to sustain its current growth composition.

Europe has also relied on a robust trade surplus to sustain growth. Coming out of the financial crisis, a weak euro and a collapse in domestic demand drove a surge in net exports, as did labor reforms enacted in Germany in 2003 that helped sustain a highly competitive, advanced manufacturing base. This played a key role in driving Europe’s recovery from the financial crisis, even as the domestic economy remained mired in a deleveraging, and more broadly net exports have been comparable in importance to domestic consumption in driving European growth over the past 15 years. Now Europe is also facing significant headwinds to this growth model from two ends—on the supply side, China’s industrial policies are increasingly placing competitive pressure on key European industries like the auto sector, and on the demand side, there is a real possibility of new Trump administration tariffs on autos and more broadly.

Trade wars tend to be worse for growth in surplus economies than in deficit economies, as their exports are vulnerable, and though tariffs are a headwind to growth everywhere, deficit economies can at least experience offsetting benefits like increasing domestic investment and onshoring of supply chains. The chart below shows the case study of the Great Depression-era trade war that began with the US’s enactment of the Smoot-Hawley tariffs. As you can see, surplus economies (including the US at the time) were more vulnerable to tariffs and the imposition of protectionist measures, and generally faced deeper economic slowdowns than deficit economies. (Though there were other drivers too, like the UK moving faster to get off the gold standard than the US.)

Longer Term, Retaliation to Mercantilist Measures Will Likely Extend Beyond Trade Measures

A key dynamic of trade wars is that the trading partner with the trade deficit tends to have the upper hand, as they have more imports to tariff than their trading partner. But in scenarios where policy makers facing tariffs choose a strategy of “escalating to de-escalate,” this means there is a clear incentive to look beyond tariffs in choosing how to respond. We don’t yet have much explicit information on how policy makers in China and Europe are thinking about reacting to new Trump tariffs, as they have been reluctant to make public statements and are likely to start by seeking to appease Trump with various “deals” to ward off tariffs. But in the event of a tit-for-tat escalation, the table below outlines a range of possible measures policy makers could pursue in response to US tariffs, including examples of those forms of retaliation from the recent past.

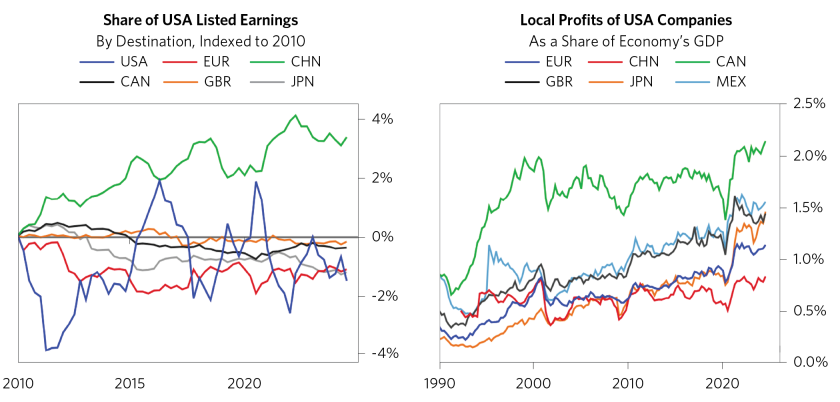

One of the most important areas to watch as this tit-for-tat dynamic plays out is the global profits of US companies. A key driver of US equity exceptionalism has been US mega-companies’ ability to earn profits abroad, as companies like Amazon, Alphabet, and Meta face few direct competitors. In a world of relatively free markets, these companies have done well by providing by and large the best services. But in a world where policy makers are increasingly focused on protecting their own national champions and finding ways of retaliating against tariffs with measures that create particular pain for US policy makers, the global profits of leading US companies are increasingly at risk. For example, tariffs could spur European policy makers to more fully pursue their existing objectives related to regulating Big Tech companies, with less concern for US opposition. They could maintain or increase digital services taxes, as opposed to rolling them back as part of the OECD tax agreement negotiated by Treasury Secretary Yellen. Or they could pursue more aggressive antitrust measures, like the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act.

The charts below put the sizing of US companies’ global profits in perspective—the top charts show that while the share of global spending that global companies have captured as profits has remained relatively flat since the financial crisis, US companies’ share of those global profits has risen in that period. The bottom charts show that the share of spending captured as profits by US companies has risen in most countries and that US companies have seen an outright rising share of earnings from China since 2010. These profits are at risk in a mercantilist world.

This research paper is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives, or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, Bridgewater's actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This material is for informational and educational purposes only and is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned. Any such offering will be made pursuant to a definitive offering memorandum. This material does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual investors which are necessary considerations before making any investment decision. Investors should consider whether any advice or recommendation in this research is suitable for their particular circumstances and, where appropriate, seek professional advice, including legal, tax, accounting, investment, or other advice. No discussion with respect to specific companies should be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular investment. The companies discussed should not be taken to represent holdings in any Bridgewater strategy. It should not be assumed that any of the companies discussed were or will be profitable, or that recommendations made in the future will be profitable.

The information provided herein is not intended to provide a sufficient basis on which to make an investment decision and investment decisions should not be based on simulated, hypothetical, or illustrative information that have inherent limitations. Unlike an actual performance record simulated or hypothetical results do not represent actual trading or the actual costs of management and may have under or overcompensated for the impact of certain market risk factors. Bridgewater makes no representation that any account will or is likely to achieve returns similar to those shown. The price and value of the investments referred to in this research and the income therefrom may fluctuate. Every investment involves risk and in volatile or uncertain market conditions, significant variations in the value or return on that investment may occur. Investments in hedge funds are complex, speculative and carry a high degree of risk, including the risk of a complete loss of an investor’s entire investment. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a complete loss of original capital may occur. Certain transactions, including those involving leverage, futures, options, and other derivatives, give rise to substantial risk and are not suitable for all investors. Fluctuations in exchange rates could have material adverse effects on the value or price of, or income derived from, certain investments.

Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private, and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include BCA, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Bond Radar, Candeal, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., China Bull Research, Clarus Financial Technology, CLS Processing Solutions, Conference Board of Canada, Consensus Economics Inc., DataYes Inc, DTCC Data Repository, Ecoanalitica, Empirical Research Partners, Entis (Axioma Qontigo Simcorp), EPFR Global, Eurasia Group, Evercore ISI, FactSet Research Systems, Fastmarkets Global Limited, The Financial Times Limited, FINRA, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, GlobalSource Partners, Harvard Business Review, Haver Analytics, Inc., Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), The Investment Funds Institute of Canada, ICE Derived Data (UK), Investment Company Institute, International Institute of Finance, JP Morgan, JSTA Advisors, LSEG Data and Analytics, MarketAxess, Medley Global Advisors (Energy Aspects Corp), Metals Focus Ltd, MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Neudata, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Pitchbook, Rhodium Group, RP Data, Rubinson Research, Rystad Energy, S&P Global Market Intelligence, Scientific Infra/EDHEC, Sentix GmbH, Shanghai Metals Market, Shanghai Wind Information, Smart Insider Ltd., Sustainalytics, Swaps Monitor, Tradeweb, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Verisk Maplecroft, Visible Alpha, Wells Bay, Wind Financial Information LLC, With Intelligence, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, World Economic Forum, and YieldBook. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.

This information is not directed at or intended for distribution to or use by any person or entity located in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability, or use would be contrary to applicable law or regulation, or which would subject Bridgewater to any registration or licensing requirements within such jurisdiction. No part of this material may be (i) copied, photocopied, or duplicated in any form by any means or (ii) redistributed without the prior written consent of Bridgewater® Associates, LP.

The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.