Over the last six months, countries like the US that have stimulated most aggressively via the fiscal lever have experienced much faster recoveries than those like Europe that have not. As we look ahead, we see continued need for fiscal stimulation as economies remain depressed, and we expect that ultimately governments will stimulate more. In the near term, however, the risks are tilting toward doing too little. In the case of the US, political infighting is leading to a pullback in fiscal stimulation now, which is creating a meaningful drag at a time when levels of activity are still unacceptably low. In the case of some other developed economies, the problem is less that fiscal policy is being withdrawn and more that it was never enough to begin with—leading to even more depressed economies.

In this research paper, we look at how fiscal policy is working across countries. We show how it has led to significantly better outcomes in countries that pushed more aggressively, and that the policies that had the most impact in offsetting the fast declines in incomes from the pandemic were ones in which money was pushed out rapidly and comprehensively, particularly directly to households, which were most likely to spend it (the US, Canada, and Japan being the main examples).

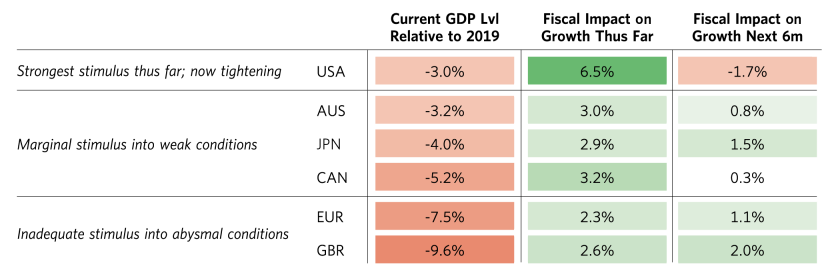

The table below shows the current level of GDP across countries and our measure of the growth impact of fiscal stimulus thus far, as well as our projections for the next six months. It highlights how fiscal support in the US has been materially larger than anywhere else but is already beginning to fade. In the rest of the developed world, fiscal supports were materially smaller; we see them continuing to rise marginally before fading next year.

As we review the effectiveness of fiscal stimulation across countries, the main differentiating factors we see are speed, size, and program types. Countries that rapidly ramped up direct government spending, job-retention programs, and household transfers have been able to both get more money spent and also stave off second-order consequences. On the other hand, places like the UK and Italy, for example, are increasing spending now, but were very slow to enact meaningful transfers and mostly relied on less effective lending guarantees. As a result, their drawdowns were much worse and levels of activity remain much lower. In contrast, for example, the US passed its first massive package at the end of March, and by the end of April had already disbursed hundreds of billions of dollars to households and small businesses—contributing to a shallower trough in conditions and faster bounce-back.

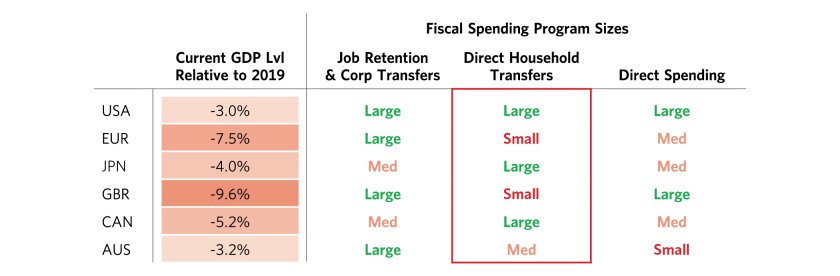

The table below highlights that the countries that were more comprehensive in covering the shortfalls in income with fiscal transfers have produced better economic outcomes. In particular, countries that incorporated large transfers to households to ensure that household income did not fall achieved more rapid recoveries.

The chart below shows that the economies that have increased household incomes through transfer programs (in addition to other programs) have seen higher spending and faster recoveries. The outlier is Australia, which had better success containing the virus and needed smaller transfer programs as a result.

What follows is a deeper dive into the fiscal picture across the major developed economies.

US’s Fiscal Response: Massive and Effective So Far, but in Need of Reload

As we look across developed world fiscal responses to the crisis, the US stands out as one of the most forceful responders due to the size, speed, and breadth of fiscal measures thus far. Successive US packages focused on pumping money to where it was most needed and did so through highly effective cash transfers (versus less effective loan programs). The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP)—a forgivable loan scheme for SMEs that didn’t lay off workers—proved a popular and effective program in stemming job losses, while transfers to households in the form of recovery checks and expanded unemployment insurance have more than filled the short-term household income hole. At the same time, massive healthcare transfers have upped response capacity considerably.

Thus far, the US has seen a sharp recovery, as enormous fiscal stimulus has helped limit second-order effects from the initial downturn. But now, many of the initial programs enacted in March have expired, and as they’ve lapsed, the recovery has slowed significantly. Moving forward, fiscal stimulus must be reloaded to prevent a sharp slowdown or reversal of the pace of the recovery. But at this point, the odds of a Phase IV package being passed prior to elections in November have fallen to near zero. If a stand-alone Phase IV package is not passed by October 2, the date on which Congress is due to recess, it likely will not get done, at least not before a new administration.

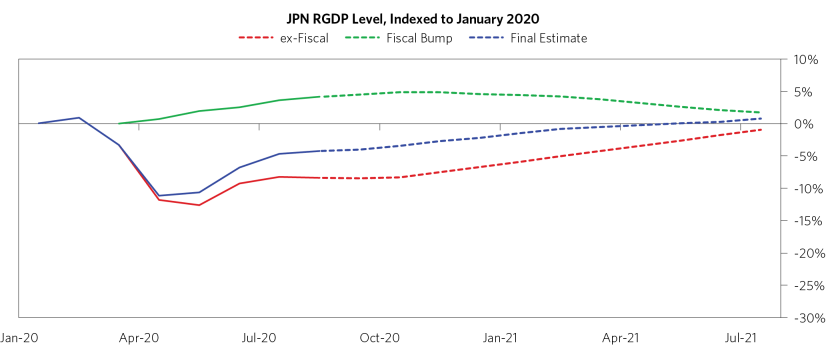

Japan’s Fiscal Response: Large Relative to More Limited Virus Hit; As PM Suga Takes Over, Fiscal Stimulus Efforts Seem Likely to Remain Robust Relative to Ongoing Drags

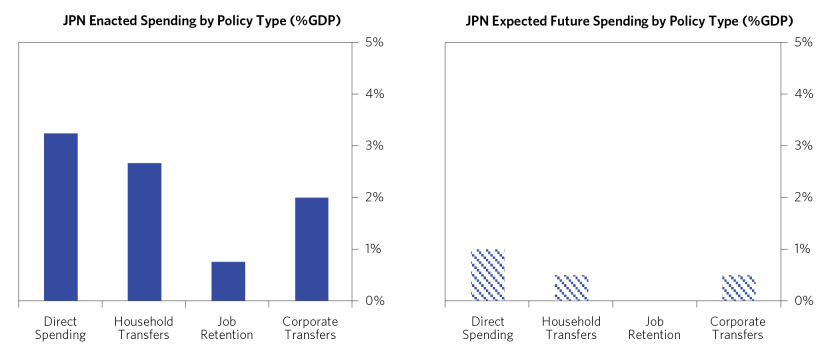

Japan’s fiscal response to the crisis has been large, consisting of three key prongs: 1) massive loan guarantees backing very cheap and favorable loans through a well-coordinated public-private bank channel, 2) sizable direct cash transfers to all households, and 3) cash transfers to smaller SMEs. Japan is a textbook case of accepting mediocre economic outcomes by not easing sufficiently, but the actions taken this time around are much larger and more aggressive than in the past. So far, the measures taken, as well as Japanese firms’ reluctance to lay off workers to begin with, have provided enough support to prevent job losses. Without a spike in unemployment and with the stimulus checks delivered to nearly every household, household incomes are being cushioned.

The question moving forward is what the next round of stimulus will look like as Yoshihide Suga takes over as prime minister. Policy makers have expressed commitment to maintaining easy fiscal policy; Japan has nearly 2% of GDP available in pre-allocated funds to spend, and Suga has expressed the desire for further stimulus centered around structural reform and competitiveness. We expect many of the pre-allocated funds to be used on a mixture of employment-adjustment subsidies, benefits for SMEs, and direct spending on the healthcare system. We’re watching the next round of structural reform for signs of how Suga is likely to govern.

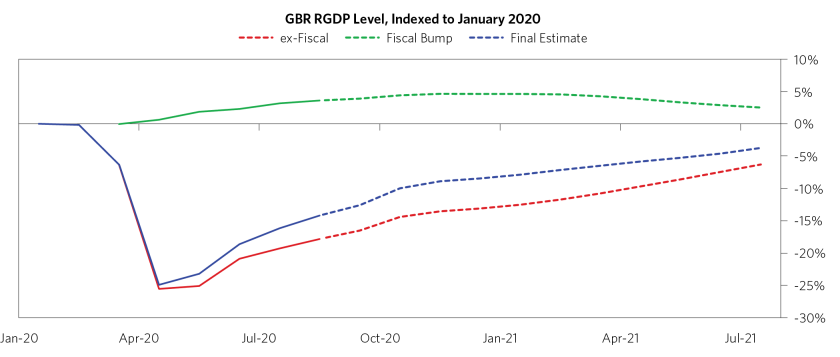

UK’s Fiscal Response: Weaker Than Elsewhere in the Developed World Particularly Relative to Extreme Economic Drawdown

The British response to the crisis was timid at first, then turned more forceful, but the response remains weaker than elsewhere in the developed world given how depressed conditions are. Ultimately, the UK is spending a lot of money now, but the delays and inadequacy of the initial response contributed to a drawdown in GDP of over 20% and current levels of activity that remain weaker than in nearly every other developed world country.

Britain enacted two flagship programs during the first phases of the crisis. The first was a job-retention scheme that effectively put workers on government payrolls to prevent layoffs between March and October. The second was a set of loan-guarantee schemes via the BoE and the publicly owned British Business Bank (BBB). The job-retention scheme has seen substantial take-up, with over 9 million workers receiving support (around 25% of the total labor force), while the lending and loan-guarantee schemes have less than a third of the £330 billion pledged. After the initial programs proved insufficient to avoid massive contractions in activity, the UK unveiled its Summer Economic Update, with a big focus on incentivizing rehiring and, to a lesser extent, stimulating demand. Our current read on fiscal conditions is that the impact of those programs has ramped up and, all told, is adding up to about a 4% impact on GDP, which is high relative to some other developed world countries but low relative to the depressed levels of conditions in the UK economy.

Compounding our concerns, the UK is at risk of limiting further fiscal stimulation: policy makers seem intent on allowing the job-retention scheme to expire in October, and Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak has also discussed a desire to raise corporate taxes. Needless to say, we think a fiscal tightening into incredibly depressed conditions would produce disastrous outcomes, and our base case remains that the UK is likely to enact another stimulus package (smaller, in the 1-2% of GDP range) providing some type of relief for workers (perhaps replacing the job-retention program with an expanded unemployment insurance scheme in addition to the rehiring incentives). But if policy makers forge ahead with a fiscal tightening, the consequences could be significant.

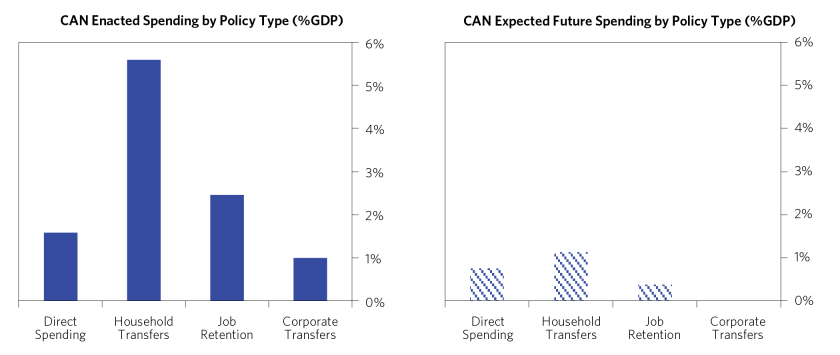

Canada’s Fiscal Response: Large and Well-Balanced Boost to Growth Thus Far, Unlikely Either to Be Ramped Up or Withdrawn Rapidly

Canada’s fiscal response was large, well-targeted, and rapidly ramped up, resting on three main programs: 1) a subsidy to corporates that retain workers, covering 75% of wages, 2) grants, loans, and loan guarantees for businesses, and 3) a new unemployment insurance scheme (CERB) of $2,000 per month for impacted workers, plus a similar offer to students. Similar to the US, the speed at which Canada was able to pass programs and disburse funds has been a key ingredient in the effectiveness of the response and relative current levels of activity. Canada’s response is also one of the more comprehensive (for instance, it is one of the few countries that have enacted both a national program for rental assistance for small businesses and forgivable loans to SMEs). Finance Minister Bill Morneau has signaled flexibility in modifying the existing schemes as the economy moves toward reopening, but uncertainty remains as to how the transition will unfold. Already, Canada has extended CERB, which was set to expire at the end of August, but at a less generous rate.

Given that Canada was so successful at pushing money into the economy (household incomes skyrocketed by 10% in the second quarter), the need for further stimulus is somewhat smaller relative to countries that didn’t adequately stimulate to begin with—though conditions remain weak in level terms. And Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has indicated that he wants to continue to stimulate, unveiling a plan on Wednesday to extend Canada’s pandemic stimulus programs through next year while also promising to create 1 million new jobs and expand support for households. But political support for further spending is unclear—conservative lawmakers have voiced concern over additional spending when Canada is already experiencing record deficits. As with other countries, our base case is that another package will be passed this fall, but we are monitoring the situation.

Australia’s Fiscal Response: Robust Relative to Limited Virus Drawdown; Future Stimulus Plans Likely but of Smaller Magnitude

Australia’s fiscal response is built primarily around a flagship employment-retention scheme—the “JobKeeper Payment”—that because of its size, regularity (twice per month), and targeting (transfers to smaller firms experiencing a revenue hit) is primed to prevent credit issues among businesses and is supporting household incomes of those who might otherwise be laid off. On the corporate/SME side, the retention scheme is complemented by the two next-largest programs: grants to SMEs and loan guarantees to SMEs. These programs have terms that will probably inhibit their effectiveness (e.g., the grants aren’t well-targeted, and the guarantees cover only 50% of loans), but they should still serve as decent supports to the larger retention scheme. For households, the retention scheme is complemented by other smaller transfers to the poor and the unemployed. Similar to the US and Canada, household incomes have risen in Australia, as expanded unemployment insurance and other direct transfer schemes have offset the private sector drawdown.

Moving forward, Australia has extended its JobKeeper program through March, as well as expanded unemployment insurance—but at less generous transfer rates. And as the country has grappled with a second wave, individual states (in particular Victoria, where the outbreak has been concentrated) are moving forward with their own stimulus packages. But the central government retains a slightly hawkish bent, with Prime Minister Scott Morrison having expressed a desire for fiscal discipline and a resistance to stimulating further. As in other countries, we think Australia ultimately will introduce a fiscal package this fall that provides some additional support (in particular bringing forward planned income tax cuts that were to be phased in over the next five years)—but the political position of conservative politicians will diminish the size of the package and may force more states to go it alone.

Europe: Mixed across Countries as Many Contend with Second Wave; Strength in Germany and France Offset by Insufficient Responses Elsewhere

Essentially all EU member states have enacted short-term work programs and large lending programs. In countries like Germany and France, these programs have been effective counterpunches and have already been extended through next year to avoid fiscal cliffs this fall. But in other economies, particularly those with high degrees of pre-existing weakness and limited ability to run large deficits (e.g., Italy and Spain), initial responses have been too small and/or ineffectively administered.

Moving forward, the EU recovery fund is likely to be a significant support to growth, particularly in economies where the fiscal response is otherwise lacking. The funds available are substantial—in some places over 10% of GDP over the next few years—and if policy makers can effectively direct them toward productive spending on projects like infrastructure and structural reforms, they could prove highly effective. But questions remain about how the money will ultimately be spent, and when. Funds aren’t expected to arrive until early 2021 at the earliest, and if politics or administrative delays push the spending timeline out, the continent may be stuck with depressed conditions for an extended period of time.

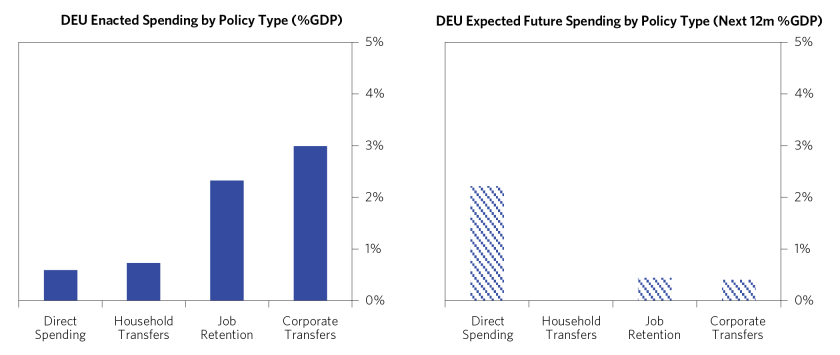

Germany’s Fiscal Response: Last Country in, First out, Thanks to Tried-and-Tested Automatic Stabilizers

We see Germany’s spending as large, targeted, and administered well enough to mitigate a downward economic spiral. Their package targets corporates through automatic stabilizers, capital injections, and loans. Overall, the programs are flowing to companies and operating effectively as intended. The government had pre-existing pipes to these corporates, and this has helped get money out fast. The main automatic stabilizer is their underemployment program, a wage subsidy called Kurzarbeit, which is experiencing large take-up and proved effective during the global financial crisis. Small businesses are rapidly making use of a hardship fund (which provides grants to struggling micro-enterprises and SMEs), while large businesses are using loans facilitated through the KfW, where a portion of lending has been bumped up from 80-90% guaranteed to 100% guaranteed (although take-up has been relatively limited so far and, as in other countries, mostly used as a backstop).

In its second supplemental budget, Germany complemented its earlier stimulus by providing targeted income substitution schemes (one-off cash transfers to parents), tax incentives (temporary VAT cuts), additional support for state and local governments, and other measures. We estimate that we’re at or nearing the peak impact of these schemes, which aim to create a floor under demand in the short term. Moving forward, the budget also outlined a large increase in public investment, mostly scheduled for 2021, aimed at enhancing productivity and growth as Germany transitions out of the immediate crisis. Germany also plans to use EU grants to supplement its own fiscal measures—though Germany is likely to receive a smaller allocation of funds relative to the size of its economy.

One thing to keep in mind with Germany, and France as well, is that these countries use job-retention programs as automatic stabilizers (i.e., they don’t require new authorization to fund), though in the current crisis they’ve significantly expanded the programs. We don’t show auto-stabilizers in the charts below, which are intended to reflect new spending authorized in response to the virus rather than pre-existing programs (so we do show funds allocated toward expanding the programs). As a result, our headline fiscal impact numbers understate the effectiveness of the fiscal response, due to the high baseline impact of existing counter-cyclical schemes.

France’s Fiscal Response: Centered on Effective Job-Retention Scheme and Corporate Lending, and Going Forward Bolstered by New Programs and EU Funds

France’s fiscal approach mirrors that seen in many European countries, focusing on job-retention schemes (which have been expanded), checks to the self-employed, loan guarantees and other small tax changes targeted at corporates, cash transfers to the smallest companies, and a reliance on public banks for capital injections into struggling firms. In France’s most recent supplemental budget, emphasis has been placed on sector-specific support, targeting the automotive, aerospace, and tourism industries via public lenders.

As with much of Europe, the job-retention scheme has been effective in preventing a rise in unemployment, and take-up in France has been among the highest in Europe. The scheme was also enhanced in June and is now set to last for the next two years—an extension we expect to see replayed in many European economies as policy makers transition into the next phases of their economic response.

Additionally, France recently released plans to utilize EU recovery funds as part of a €100 billion “Relaunch France” package intended to stimulate beyond just counteracting the effects of the virus. The plan centers around a combination of virus mitigation spending (“Cohesion”), green investment (“Environment”), and structural reforms intended to raise France’s potential growth rate (“Competitiveness”). The French government thinks it will boost GDP by about 1.5% annually over the next two years, and our estimates reflect that it’s likely to be an effective mix of policies.

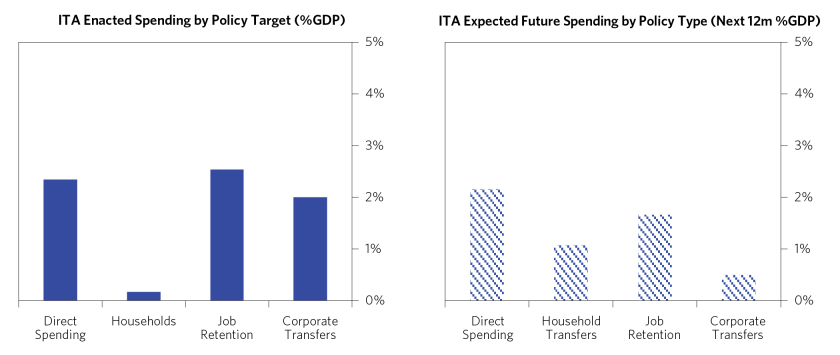

Italy’s Fiscal Response: Month-to-Month Response That’s Probably Too Small to Fill the Economic Hole

Italy has so far announced a lot of fiscal measures, but we think they are overstated, poorly timed, and not designed well to fill the hole. The Italian Treasury is between a rock and a hard place: on the one hand, it needs to ease fast, but on the other hand it also needs to ensure that a reluctant ECB will fund the deficit before it can issue, as it is worried about private markets’ ability to absorb it (though those worries have eased as spreads on Italian debt have compressed). As a result, it has adopted a month-to-month approach, announcing a small package for job-retention schemes in March (€20 billion), a massive but unfunded loan-guarantee program in April (€400 billion), and a larger package of transfers in May (€55 billion). While the numbers aren’t small, they are not big enough relative to the huge hit the economy took in recent months, and we have questions about the Treasury’s ability to funnel the money effectively and in time. As mentioned, the loan guarantees are unfunded, and even public banks have been reluctant to extend credit without a stronger commitment from the Treasury.

As in places like the UK, delays in passage and implementation of meaningful stimulus (even just the month or so delay before the passage of Italy’s primary transfer package) have proved costly, as Italy experienced one of the worst drawdowns in activity across major economies. As in the UK, our current estimates reflect that the peak impact of policies passed thus far is likely to occur over the second half of the year (starting roughly now).

Moving forward, Italy stands to be one of the largest beneficiaries of EU recovery money. It is set to receive nearly 25% of the total funds, adding up to nearly 15% of Italian GDP over the next three years or so. Similar to France, we expect the funds to be used on a combination of measures to mitigate the ongoing economic effects of the virus, as well as strategic long-term investments in competitiveness and support of strategic industries like green energy.

Spain’s Fiscal Response: Likely to Be Big Beneficiary of EU-Wide Stimulus

Despite a severe virus outbreak, Spain has been much less generous in providing fiscal support than its European counterparts, hampered by policy makers’ belief that pre-existing deficits limit the government’s room to maneuver and by a weak minority government. The two main pillars of its response are a loan-guarantee program and an expanded furlough scheme known as ERTE.

As with Germany and France, Spain has updated its existing short-term work scheme, loosening firm eligibility requirements, increasing benefit generosity, and broadening coverage (including workers in non-standard jobs). According to the most recent data, the program has been relatively effective compared with its European counterparts in reactivating furloughed workers—nearly three-quarters of the 3.4 million people enrolled at the height of Spain’s lockdown in April have since returned to work.

Despite the scheme’s apparent success, the government barely managed a three-month extension before it expired on July 30—underscoring the risks around Spain’s fiscal cliff and the importance of EU-wide stimulus measures, of which Spain is expected to be a major beneficiary. We expect Spain to spend nearly 15% of GDP in EU stimulus funds over the next few years, frontloading as much of the spending as possible given where conditions are. The specific mixture of policies, and Spain’s ability to funnel the money toward growth-additive spending and investment, will be a key determinant of future economic outcomes.

This research paper is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, Bridgewater's actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This report is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned.

Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Capital Economics, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., Consensus Economics Inc., Corelogic, Inc., CoStar Realty Information, Inc., CreditSights, Inc., Dealogic LLC, DTCC Data Repository (U.S.), LLC, Ecoanalitica, EPFR Global, Eurasia Group Ltd., European Money Markets Institute – EMMI, Evercore ISI, Factset Research Systems, Inc., The Financial Times Limited, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, Inc., Haver Analytics, Inc., ICE Data Derivatives, IHSMarkit, The Investment Funds Institute of Canada, International Energy Agency, Lombard Street Research, Mergent, Inc., Metals Focus Ltd, Moody’s Analytics, Inc., MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Renwood Realtytrac, LLC, Rystad Energy, Inc., S&P Global Market Intelligence Inc., Sentix Gmbh, Spears & Associates, Inc., State Street Bank and Trust Company, Sun Hung Kai Financial (UK), Refinitiv, Totem Macro, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Wind Information (Shanghai) Co Ltd, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, and World Economic Forum. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.

The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.